Memoirs

Memoirs

Here you’ll find a collection of my memories about my family, in no particular order, with no particular rhyme or reason.

My maternal grandparents

Grandfather was born Velvel Sclaterovitch. In England he was known as William Sclater and later, William Goldberg in the United States.

Grandmother was born Rifka Levin and became Rifka Goldberg when she married my grandfather.

My mother’s father was a Hassid who came from Riga, Latvia where he was named Velvel Sclaterovitch. In the 1870s or 1880s he met my grandmother while walking through Lithuania and fell in love. She was a Misnagid named Rifka Levin living in Eishyshok, a town near Vilna. (In Israel they would be called a Mitnagid since Israel has adopted the Sephardic pronunciation. However, I am used to the Litvak or Lithuanian Yiddish so she was a Misnagid.) Marriages had been arranged for both of them. That became as nothing. Ruth said to Naomi, “Your people shall be my people.” My grandfather cast off his Hasidism. Rivke was a Misnagid. OK. He was now one, too.

The Misnageddim were under attack from the Hasidim. One must be careful in referring to the Hasidim to realize that various Jewish groups at different times in history with no connection to each other have called themselves Hasidim which means pious. The Hasidim I am referring to and which my grandfather started out as was inspired by Baal Shem Tov. He appealed to the unlearned and ignorant by rabbinic standards. He emphasized devotion over learning. Their mysticism opposed the Misnaggedim’s rationality. The Vilner Gaon actually issued a herem or excommunication against the Hasidim. The herem is the most potent weapon Judaism has against the dissident. However, the Hasidim and Misnaggedim both followed halakhah (Jewish law) and joined ranks against modernity. Their descendants are prominent in the religious right in Israel.

The Misnaggedim were under attack from another direction, the modernising influence of the Haskalah. Moses Mendelsohn started the Haskalah in the middle of the eighteenth century. The Haskalah or Enlightenment was the movement to disseminate European culture among Jews. It advocated the modernization of Judaism, the Westernization of traditional Jewish education, and the revival of the Hebrew language. The Gaon resisted the introduction of secular subjects into the curriculum of Jewish schools. However, he was fighting a losing battle. Even that Misnagid, Levin, taught his students about nature, and his daughter was interested in history along with other secular knowledge. The Misnageddim thought of Hebrew as a sacred language that would be degraded if used for other purposes than study and discussion of sacred matters. Even Herzl in Der Judenstaat did not think of Hebrew as the language of the state. He thought of a country like Switzerland where different cantons would have their own language and culture. Jews who came from various cultures would go to separate enclaves and like Switzerland not have one national language.

Misnaggedim means “opponents.” Actually they were more than that. They were simply supporters of traditional Judaism - a religion of law. However, to support the law one has to know the law. In learning the minutiae of law one can be unaware of its application.

A case in point was the story of Malke, a widow with several children. In the traditional Jewish society no man or woman of marriageable age should be without a mate so the saintly Rabbi Yossef Zundl Hutner and his wife found a fine young scholar from the Yeshiva for her. Malke had been supporting her family on the income from the store, which, like the other stores in Eishyshok, had its biggest earnings on market day. On the first market day after their wedding Malke’s husband left the beth midrash to assist his wife for a few hours at the store. It was the first time in his life he had faced a real scale. Though he knew all the halakhic and ethical regulations pertaining to scales, he did not in fact know how to use one, as his wife discovered when she gave him a kilogram of salt and he carefully placed both the salt and the weights on the same side of the scale.

Malke was outraged. In an unprecedented move she closed the store on market day, grabbed her husband by the sleeve, and marched him through the market square to the home of Reb Zundl. When she arrived at the rabbi’s house, she said, “Rebbe, you gave him to me. You take him back. I am a hardworking widow who has to provide for her orphans so that they will grow up to be proper human beings. I do not have the time to raise yet another child.” She left her husband with the rabbi and was eventually granted a divorce.[1]

Back to grandfather.

Velvel went to England and promised that he would send for Rifka. In England he remained a poor Jew.

Moses Montefiore was a rich English Jew who was embarrassed by the presence of the poor eastern European Jews who fled to England. He gave my grandfather enough money so he could get second-class passage to the US.

If a passage was better than steerage at the time my grandfather came to the US, there were no immigration formalities. Grandfather got off the ship at Castle Garden (predecessor to Ellis Island) in lower Manhattan and was free to go where he would.

Grandfather used the name of William Sclater in England and William Goldberg in the United States. A friend of his came to meet him at the boat. The friend said he was his brother. Since its customary to have the same name as a brother, he became Goldberg.

After grandfather came to the United States he got a supply of goods from, I think it was Sam Rosoff in New York City. With those goods he peddled in the Adirondacks. He took the train from New York City to the Adirondacks.

He used to walk through the woods with his suitcases. He called them ports or telescopes. He would visit isolated farmhouses and sell them things.

He was taken by the beauty of the mountains and apparently loved to be there. The itinerant pedlar was generally welcome as he was a source of news from the outside world. Quite often he would sleep in the woods.

After accumulating some money he sent for my grandmother. As will happen she became pregnant. Early in her pregnancy they decided the lower east side of New York City was not a proper place to raise children. They moved to Brandon, NY in the Adirondacks, a settlement of about six families, not on any paved road. Brandon no longer exists, but that's where my mother was born on March 6, 1898.

Even though they lived in a village where all the other people were French Canadians they remained observant Jews. A schochet (ritual slaughterer) occasionally visited to slaughter their animals and those of other isolated, observant Jews. My grandmother cooked some typical French Canadian dishes such as Johnny cake. Possibly the French Canadian housewives made gefilte fish. Brandon was on the edge of the Rockefeller estates.

The Rockefellers wanted the land so Rockefeller thugs harassed people.

They didn’t physically attack them, but they destroyed their crops, killed their live stock and in general made their lives miserable. Brandon had a post office which was a small room in one of the houses. The Rockefellers got the government to eliminate the post office so residents of Brandon had to go to town to get mail.

My mother's family & the family of 'French Tom' were the last to leave. People finally moved out, and Brandon became part of the Rockefeller estates. Later it became part of Adirondack State Park. I visited Brandon once. There were six depressions in the ground where houses once stood.

Since the town hall at Tupper Lake, NY was burned down mother’s birth records are unavailable.

I have looked up relatives who might know bits of family history that I don’t. My cousin Barry told me that he heard they had a cow called Shakespeare. He could not tell me the reason for the name. They had a horse called Jerry. When Jerry got too old to work my grandmother wanted to have him rendered. My tender hearted grandfather would have none of that. Jerry lived on in retirement until he died of old age. In Eishyshok the farmers who lived outside the shtetl were called yishuvniks. That was a term of contempt in that milieu as the yishuvniks did not have access to the religious education of the ‘proper’ Jewish male. In the United States grandmother and grandfather became yishuvniks.

Later they moved to Bloomingdale, Tupper Lake and Newman, N. Y. that became part of Lake Placid.

Lake Placid had a population of 1,500 so it was the size of a small shtetl. Much of the shtetl ethos remained with them.

The itinerant maggid in Lithuania has his counterpart in the itinerant schohet of northern New York State. My grandparents used his services when they lived in Brandon, NY and later when they moved to Lake Placid. A schohet is a ritual slaughterer of animals and poultry in accordance with Jewish law. I remember a schohet slaughtering a chicken in the cellar. In the centre of the cellar was a wood-burning furnace surrounded by a dirt floor. The only light was that cast by the flickering flames of the furnace. The schohet didn’t succeed in killing the chicken immediately, and it ran around the cellar casting weird shadows. I was frightened and fascinated.

My grandmother combined rigid observance with scepticism.

I remember her questioning both miracles and the Messiah. Orthodox Jews are not supposed to light fires on the Sabbath. One Friday in the twilight she saw my grandfather crouched down next to the woodshed smoking. She said in shock, "Goldberg, it's still shabbas!" He responded, "Goddammit to hell. I forgot!"

In that incident my grandfather was violating the law and my grandmother was concerned with observing it. Yet my grandmother was a sceptic, and my grandfather was a believer. She observed rigidly, but her mind roamed free. My grandfather was a thorough believer, but apparently his God was one who wasn't going to get his knickers in a knot if an old Jew had a smoke on shabbas. She exemplified the misnagid attention to ritual, and he exemplified the devout belief of a Hassid.

In that my grandmother was going back to early Jewish tradition in the period of Ezra after the return from Babylon. Ezra was a Jewish religious leader who worked together with Nehemiah to strengthen the community. In this case the strengthening was effected by the introduction of a number of innovations including the regular reading of portions of the Torah which appears to have been forgotten or not to have been known at all among the Jewish community in and around Jerusalem. There is a major problem in dating Ezra as there is a tradition that he precedes Nehemiah, although the story itself reads a lot more logically in his direction, leading many historians to suggest a dating in the 420s for Ezra.

“The policy adopted by Ezra and his associates and followers, of reducing all belief and practice to law, and expanding the law so as to embrace every detail of life, had a negative as well as a positive influence on the development of the doctrinal beliefs of the Jews.

I remember going around the house with grandfather looking for chometz before Pesach.

“Goddammittohell, Miltele, we can’t miss any of the chometz.” Chometz is food such as bread which a Jew is not supposed to eat during Passover. Some bread would be scattered around before the search so there would be chometz around.

The law which aimed to regulate all the actions of men, allowed their thoughts and beliefs comparative freedom.”[2]

The above quote which came from a publication of the Jewish Publication Society in 1905 indicates that the author would probably object to allowing thoughts and beliefs comparative freedom. However, that seemed to me to be precisely my grandmother’s philosophy. Obey the laws, but let your mind roam free.

Obey the laws, but let your mind roam free.

In fact that could be the motto for the democratic state. They shouldn’t care what you think as long as you obey the law. Isaiah Berlin, another Jew of Latvian antecedent, referred to this as negative liberty.

Grandmother was an earthy person. She observed that a sufficiently horny man needed only a ‘brait mit a loch’ (Yiddish for bread with a hole in it.)

She was not bound by local custom. In Lake Placid most people did not use the parlour except for formal occasions such as weddings or funerals. In my grandparent’s house we used to sit, relax, talk or read in the parlour. Before the house was electrified kerosene lamps were used.

There was a magnificent bathroom. The bathtub was long and stood on metal bird’s feet clutching glass balls. There was a large picture on the wall of a deer having a drink. It was not the popular print titled “The stag at eve had drunk its fill”. There was a book case next to the toilet containing good reading matter.

The wood burning furnace heated the house. There were louvered registers in the floors. They could be opened or closed to let the hot air in or block it. My room was at the rear of the second floor above the kitchen. The register was over the wood-burning stove. One time when grandmother was frying fish I opened the register and urinated on the fish. Grandmother shook with rage. Then she started to shake with laughter.

My grandmother provided great fun for a little boy. Line up the chairs in the kitchen, and they became a dining car on a train. “Would you like to have something to eat before we get to Albany?”

One New Year’s Eve grandmother and I were alone in the kitchen. When the clock struck midnight I banged pots and pans. Years later I was at a party in Manhattan. I left the party before midnight. At midnight I was in an almost empty subway train riding below Times Square where crowds were cheering the New Year. I thought of that past New Year long ago with my grandmother and was happy.

My grandmother told me of a vision someone once saw in a pond in Eishyshok. Other people said they saw the same vision, and it became part of village history. Then she raised questions. Did the person really see the vision or did that person want to attract other people’s attention? Did the other people see the vision or did they want to share the excitement? Although she probably never heard of David Hume she shared his scepticism.

It was a great worry to me when I became aware of mortality and thought of losing my grandmother. I can remember the odour of lineament that she used on her aching body. I remember the odour of clean clothes, garden and lineament. I keep her bottle of Sloan’s lineament.

It is the relic of a saint. Her legs were shapeless and thick with the oedema that afflicts some old people when they retain fluids. The Sloan’s helped to ease her aching body.

I asked, “Ma, why are your legs so thick?” I called her ‘Ma.’ Her children did so why shouldn’t I?

She looked at and held me close. In a dreamy voice she said, “When I was a young and beautiful woman in Eishyshok it was a beautiful starry night. I went swimming in the river. The smell of blossoms and the reflections in the water so took me that I was not aware of the nearby water mill and with drawn into the water wheel. I was so battered that my legs were no longer shapely when I got out. That’s why my legs are like this.”

I, of course, believed my grandmother. She was rigidly honest and would not lie to me. It was only years later that I realised that she did not want me to think of the infirmities of age.

My grandmother once saw me with a pencil. She asked where I got it. I told her I found it in the road. She told me to take it back and put it where I found it as the person who lost it may come looking for it.

However, her story wasn’t entirely fiction. There was a town of Eishyshok and there was a mill.

Eishyshok was founded in 1065 and the Jews in it (80% of the population) were murdered in 1941. There are gravestones dating from 1097 in the old Jewish cemetery so Jews have lived in the town almost from its beginnings. I have been able to find out about Eishyshok from Yaffa Eliach’s book There Once was a World. According to TOWAW swimming is the one athletic activity sanctioned by the cheder. A cheder taught its students the fundamentals of Judaism. In the Talmud a father is enjoined to teach his son to swim.

For a long time I thought my grandmother’s story was true because of her rigid honesty. There were people in Eishyshok with similar rigid honesty. One such person was Israel Meir Ha-Kohen (1838-1933) better known as Haffetz Haim, author of 21 books, and one of the founders of the anti-Zionist Agudat Israel. His ethical standards were extreme. Because he supported himself by selling his books, he made considerable use of the mail. When he occasionally sent books by tourists or travellers, he felt he was depriving the post office of its legitimate revenue. Therefore, before handing the books over he would weigh them complete with wrapping paper and string, and then go down to the post office to pay the money he felt he owed.[1]

I think of my grandmother, the little boy I once was and the town of Eishyshok. I would like to keep her memory alive a little longer and tell people a bit about Eishyshok. Her father was named Levin. I don’t know his first name, but I have been told some anecdotes about him.

Old man Levin saw his boots were wearing out. In the nineteenth century when a person wanted a new pair of shoes or boots he made a pair himself or went to the local shoemaker and had a pair made. Country stores in Eastern Europe didn’t sell footwear. The shoemaker pulled out hides, and the customer chose an area of hide and asked that the shoes be cut from that. Levin was a particular man who wanted the world made as right as it could be made for him. He scrutinized each hide and ran his hand over it. The shoemaker became impatient. “Reb[2] Levin, you’re ninety-nine years old. Why are you so fussy?”

“Who knows how long I’ll last? Very few people die over the age of ninety-nine.”

He was a nature lover as was his daughter. She was an avid gardener. In the Adirondacks one can have a killing frost any night of the year. During the short growing season she used to cover the garden plants with cheesecloth to protect them from a killing frost. In the winter the temperature would often go as low as –40. That’s a very convenient temperature since it’s the same in Centigrade or Fahrenheit.

Old man Levin is the earliest ancestor I have anecdotal knowledge of. I never met my great grandfather, my mother’s mother’s father. He died before I was born and lived in Eishyshok. He was a melamed (denoted a religious teacher or instructor in general (e.g., in Psalm 119:99 and Proverbs 5:13)) but a most unusual one. He took his students out, showed them the biota and told them about nature. I surmise that he was originally a farm boy.

Levin was a melamed or teacher of the sacred texts in Hebrew. Most Hebrew teachers had their students sit in the cheder and work strictly on religious texts. He took the boys out on nature walks. That was most unusual. He knew the flowers and much about nature. Czarist degrees of 1861 and 1869 took the land away from most Jewish farmers around the town.[3] Possibly he came from a farm family. He certainly was a nature lover as was his daughter. She was an avid gardener. In the Adirondacks one can have a killing frost any night of the year. During the short growing season she used to cover the garden plants with cheesecloth to protect them from a killing frost. In the winter the temperature would often go as low as –40. That’s a very convenient temperature since it’s the same in Centigrade or Fahrenheit. Jews resist conversion.

My great-grandfather’s name, Levin, indicates that a person comes from the tribe of Levi. According to the bible twelve tribes settled Canaan. The Book of Joshua describes the conquest of Canaan and the division of the land among the tribes. The tribe of Levi received no part of the land although they did have cities allotted to them.

JOSHUA 13:14 Only unto the tribes of Levi he gave none inheritance; the sacrifices of the LORD God of Israel made by fire are their inheritance, as he said unto them.

The Levites or the tribe of Levi contained the priestly class and those who assisted the priests, performed sacred music and fulfilled other functions ancillary to worship.. Legend has it that the Levites were descendents of Levi, the third of the twelve sons of Jacob. Some scholars suggest the Levites were a heterogeneous, sacerdotal guild that acquired tribal status.[4] Jews whose names are Cohen or variants such as Kahn, Kohn etc. are descendents of the priests.

When many serfs were freed they were given land. Some of the land they were given was taken from Jewish farmers. I think my great grandfather could have been one of those Jewish farmers. After the expulsion of Jews from Spain in 1492 they found refuge mainly in Poland, North Africa, Italy and Turkey. In Poland they were a desirable layer between the nobility and the serfs. The nobility wanted to keep the serfs in their status as an underclass, but a middle class to manage estates, establish small businesses and be a class between serfdom and nobility was desirable. That was the role Jews filled in Poland, and some became well off. Jews could not rise to the nobility or sink to the peasantry. However, their lot was good in general.

In my opinion Stanislaw Poniatowski, the last king of Poland was a magnificent man. He was inspired by the American and French Revolutions and wanted Poland to become a democracy. He introduced reforms such as educating the children of the serfs. The autocracies of Prussia, Russia and Austria were alarmed by the prospect of a democratic Poland in their midst and divided Poland between them in a series of partitions starting in 1792.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Partitions_of_Poland

Czarist Russia was both Jew hating and almost free of Jews in the eighteenth century. Suddenly there were many Jews living in Russia as the part of Poland that Russia absorbed contained many Jews. The Pale included the lands taken for Poland by Russia.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pale_of_Settlement

In general Jews lost the status they had in Poland, and life became more difficult for them. Great-grandfather could no longer farm and became a melamed or Hebrew teacher.

Cheder classes were strictly male. However, my grandmother listened outside the window to the proceedings. He noticed her and said, “Come in, maidel[5].” After that Rivka was part of the class. Her love for learning never left her. As far as I know she had no formal education outside of the cheder classes she sat in on. At her bedside when she died was a history of the French and Indian Wars. As much of her adult life was spent in the Adirondack Mountains with a significant French-Canadian population she wanted to learn as much as she could of the culture and history of her surroundings. She used to listen to opera. Before the days of radio they had a windup Victrola, a record player of the time, with a steel needle.

I have a history of Eishyshok since its founding over 900 years ago. It is fascinating. Lithuania was the last place in Europe to become Christian. The Lithuanians mainly worshipped Perkunas, the god of thunder and forests, who ruled over the other gods and goddesses in the Lithuanian pantheon. They were completely tolerant of those who did not believe as they did. Jews could even be nobles.

When emissaries of the pope came in 1324 to convert Prince Gediminas he told them he did not interfere with Christians who worshipped their god according to their laws, and he hoped he and his subjects would be left to worship in their way. Unfortunately Jogaila married Jadwiga, a Christian Polish princess, and Lithuania became Christian in 1386. Jews lost some but not all of their rights. Unlike the Polish Jews the Lithuanian Jews could still be landowners. Lithuania and much of Poland was absorbed by Russia in the late eighteenth century. After the serfs were freed in 1861 and 1869 Jewish owned land around Eishyshok was taken from them and given to the freed serfs. Possibly, my great grandfather's love for and knowledge of nature is due to his family living on the land before it was given to the serfs.

Yiddish only has words for the flowers, rose and violet. He probably taught them the Russian or Lithuanian names for the other flowers.

Levin was a Litvak, a Misnagid and lived in the shtetl of Eishyshok. Shtetlekh were small market towns in Eastern Europe with a mainly Jewish population. The shtetl was typically a town ranging in size from 1,000 to 20,000 and was a uniquely Eastern European phenomenon. We can trace its origins to the eleventh of and twelfth century when Jews from Babylonia, Germany and Bohemia began trickling into Eastern Europe joining the Jews of the former Khazar Empire. Many of them settled in large urban centres, and a few lived in isolated rural areas, but most would eventually make their homes in one of the thousands of shtetlekh that came to serve as trading centres for both country and city folk in the vicinity.

Lithuania was attractive to Jews. It was the one of the last places in Europe to become Christian. The Lithuanians mainly worshipped Perkunas, the god of thunder and forests, who ruled over the other gods and goddesses in the Lithuanian pantheon. They were completely tolerant of those who did not believe as they did. Jews and people of any background could be nobles. When emissaries of the pope came in 1324 to convert Prince Gediminas he told them he did not interfere with Christians who worshipped their god according to their laws, and he hoped he and his subjects would be left to worship in their way. Unfortunately Jogaila married Jadwiga, a Christian Polish princess, and Lithuania became Christian in 1386. Jews lost some but not all of their rights. Unlike the Polish Jews the Lithuanian Jews could still be landowners. Lithuania was absorbed by Russia in the late eighteenth century. After the serfs were freed in 1861 and 1869 most of the Jewish owned land around Eishyshok was taken from then and given to the freed serfs.

Levin was the quintessential Litvak or Lithuanian Jew. At least he exemplified the picture Litvaks have of themselves – a wry sense of humour cocking a snook at the trials of life. At times especially during Russian rule most of them lived in great poverty. “If a Jew eats a chicken one of them is sick.”

Other people have a different notion of Litvaks. The name has been applied to Russian Jews in general.

Alfred Döblin was a German author who was alienated from his Jewish roots. He sought to recover them by visiting Poland and observing the Jewish community in Poland and Polish society in general. In Journey to Poland p. 37 is the following:

“I sat in front of a very intelligent, very down-to-earth National Polish politician. …The Germans here are well-to-do; a highly cultivated and privileged nation, Jews and Poles were on excellent terms until 1903. Then the Jewish Russians showed up, energetic, sly, the hated Litvaks; they aroused the opposition of the Poles and the local Jews. Now they have fused with them. The Jews are unilaterally merchants, but Poland’s economic foundation is too narrow for so many merchants.

Actually all Jews were not merchants, but that is the picture that Döblin had. It is telling that an alienated German Jew would accept the picture of Jews given him by an antisemite. Döblin apparently found what he was looking for when he converted to Catholicism in 1941. I mention him because his life mirrored many that of many German Jews who were alienated from their roots. His books in my judgement are worth reading in spite of his blindness.

Jews have had a love for Germany and German culture for a long time. It’s a love that has not been requited. I have read much in preparing for essay and will not have time to hit more than a few high spots. The Companion to Jewish Writing and Thought in German Culture, 1096-1996 deals with that love. We must deal with German culture if only because Yiddish is a German dialect. Jews themselves have had a love/hate relationship with Yiddish.

Litvaks are reputed to be witty, and even the Litvak meshuggener (crazy person) had their share of wit. Most mentally ill people were not sent to institutions and lived in Eishyshok or other shtetlekh. The community or their family supported them. Eliach told about a couple of twentieth century lunatics.

Benchke the Meshugenner had a head injury while working with his oven builder father. During occasional violent attacks he would have to be put in chains. Once Benchke got in a fight with a bunch of youngsters and injured his finger. He went to the old Beth Midrash to complain. Lunatics, under the protection of the shtetl of Eishyshok, were regarded as God’s less fortunate children and were given food, shelter, clothing, compassion and free transportation after Eishyshok got a bus system. The charitable organisations in Eishyshok saw that people not competent to understand their entitlements were still received them. Among their entitlements were the right to state their grievances from the bimah of the shul or Beth Midrash. Benchke mounted the bimah, banged on the table and announced, “Either you treat me well, or you can find yourself a new lunatic!” Benchke was one of the victims of the September 1941 Nazi massacre.[6]

Arke Rabinowitch was Eishyshok’s most brilliant lunatic. He had been an artist whose paintings had won praise from the critics. When he emigrated to Palestine something happened to him, and his mind snapped. Arke was sent back to Eishyshok to live with his family. When he became increasing violent he was sent to Selo. Jewish farmers had set up a mental institution without walls in the twentieth century. Their land was poor, and it was an economic decision to set up such an operation in an attractive natural setting. Jews sent unfortunates to Selo from as far away as Warsaw. Socialists and Communists visited Arke to hear his commentaries. He greeted visitors with, “Do you come to our Utopia as an inmate or a guest?”

Since Selo as well as Eishyshok were on the Polish side of the border between WW1 and WW2 the Polish Minister of Agriculture together with his wife made an inspection of Selo. Left alone with the wife Arke complemented the woman on her looks and taste. She complained to her husband about the ‘dirty Jew’ who accosted her. The minister took out his revolver and aimed it at Arke. Arke turned to a shtetl official who was with the minister, and said, “Meischke, tell him I am a lunatic.” When the Russian took over the shtetl in late 1940 the appointment of Yoshke Aronowitch to the police amused him. Yoshke had recently had part of his intestines removed. Arke proclaimed, “If Yoshke, having no stomach can be a policeman, then I, Arke Rabinowitch, having no head, can be a government minister.” After the Germans occupied the shtetl in June 1941 Arke approached the Wehrmacht commander and announced, “If Hitler, a former painter, is now the world’s leader, then I, Arke Rabinowitch of Eishyshok, a deranged painter, is qualified to be a führer.” The commander had him shot, and Arke became the first Jew to be killed by the Nazis in Eishyshok.[7]

One measure of the decency of society is its treatment of those at the bottom. By that standard Eishyshok was a far better society than those in current Australia and the United States where homeless people many of them mentally ill wander the streets. Often rather than sympathy they rouse hostility from those who find them unsightly and an offense to tourists.

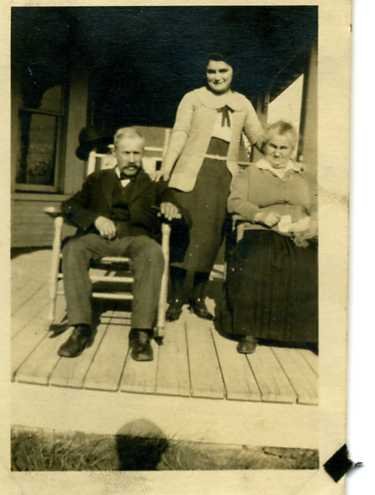

As I find out more about Eishyshok I become aware of similarities between the lives of my grandparents in the US and the lifestyle in the old country. People with mental disturbances were only sent to institutions if the family could not handle them. There was a distant relative in the US who became disturbed after an unfortunate love affair. True to her tradition my grandmother took in cousin Mary. During the periods when she was lucid enough to leave the state hospital she stayed with them. Figure 1 shows my grandmother, grandfather and Mary on the porch in the 1920s. Grandfather spent some time in England before coming to the United States. In England he picked up the idea that proper dress consisted of a three-piece suit, bow tie and derby. His derby is on one of the posts of his rocker. He had a great admiration for Queen Victoria and referred to her as “die mammeh.” I wish I could tell him I’m living in Queensland since Victoria is the queen whose land it is.

Hate them or love them Litvaks are thought of as intelligent. Maggidim were itinerant intellectuals, rabbis and scholars, who delivered sermons as they travelled and supported themselves on the donations from such activities. It was a big event when a maggid came to town. The Maggidim were gadflies who carried on dialogues with all levels of society. Even the renowned Gaon of Vilna was an admirer of the maggid of Dubno, Yaakov ben Wolf Kranz, [1741-1804]. There was even a special genre of stories involving the maggidim. Here’s one from Yaffa Eliach’s book, There Once was a World:

There once was a maggid who always traveled from shtetl to shtetl with the same coachman. Since the maggid used to practice his sermons aloud, the coachman became familiar with his entire repertory. One day the maggid suggested that he and the coachman exchange roles. When they arrived at a nearby shtetl, it was the coachman who mounted the bimah, dressed in the maggid’s clothes to deliver the sermon, while the maggid stood near the door of the beth midrash, the coachman’s whip in his hand and the coachman’s clothes on his back. The coachman delivered a very fine sermon which pleased the audience greatly. At the conclusion of the sermon, a young man approached the bimah and addressed a scholarly question to the maggid, who was quick to respond: “Such an easy question even my coachman can answer,” he said motioning to the “coachman” to approach the bimah.[1]

That story illustrates the trust the maggid placed in a simple man. The shtetlekh had a rigid class structure. Near the bottom were baalegolehs or coachmen. They made their living in the nineteenth century by carting goods and people from place to place in horse drawn wagons. It also illustrates the concept that quickness of mind characterised Litvak society from top to bottom.

My grandparents loved the Adirondacks and are buried along with my mother and father in a Jewish cemetery in Whitesboro, NY which overlooks the foothills of the Adirondacks. Grandmother died in 1936. She did not survive a goitre operation.

Mountainous areas are usually short of iodine. A shortage of iodine affects the thyroid gland and is a cause of goitre. At the present time salt is routinely iodized so goitres have almost disappeared. Grandfather was a jovial man fond of multilingual puns. He laughed a lot. He didn’t die until 1943, but I never heard him laugh again after grandmother died. The love of his life was dead.

He was buried in winter with deep snow on the ground. The coffin was moved to the burial site on a toboggan. He was a sporty fellow and would have loved the toboggan ride had he been aware.

I have fond memories of my grandfather reading the Forward in Yiddish and was delighted to find the Forward website.

I can remember my grandparents having an argument. Dishes were flying, and I was frightened. Grandmother stepped back, made a funny face, and pointed her finger at Grandfather. Then they both dissolved in laughter. My parents argued in dead earnest, but my grandparents just let off steam.

I have often wondered why my mother seemed so different from her parents. Perhaps a clue lies in anthropology. People two generations removed can react as a ‘joking generation’. The tensions of parenthood are absent. Google ‘joking generation anthropology’ to find out more.

Yiddish was the common parlance of most Jews. Yiddish is a German dialect that Jews who lived in Germany developed as a lingua franca with the surrounding area. Yiddish had Hebrew and other words of non-German origin mixed in. As Jews moved out or were expelled from where they lived in Germany they kept the language but modified it adding local words and changing pronunciations mainly the vowel sounds. Yiddish was the mameloshen (mother tongue). Children heard it from their mothers. Boys got a religious education that involved study of the sacred literature in Hebrew/Aramaic. Their mothers and sisters did not know Hebrew except for a few prayers such as those over the Sabbath candles.

Mother called Yiddish a jargon and would try to substitute a proper German for it. That could have been Haskalah behaviour. As my grandparents lived in the isolated community of Brandon where the other families all spoke French as they were French Canadians my mother learned French before she spoke English. She tried to distance herself from both Yiddish and Canadian French. In the future was a Nobel Prize for a Yiddish writer and recognition that Canadian French preserved more of the language of Moliere and Racine than the European French of today. However, the melting pot ideology prevailed and 'real' Americans put aside other languages. Ironically my mother's English was tinged with Scottish expressions. Her first teacher in a one room school was a Scot from Ontario, and my mother would say things like wee and sma' for small.

Mother was the first member of her family to go to university, and she went to Elmira Female College and later Plattsburgh Normal. At the time she went to university the main jobs for educated women were as a teacher, nurse or librarian.

Mother was teaching at the St. Regis Indian Reservation which like Ogdensburg is on the St Lawrence River. It was the age of assimilation. Everyone including Native Americans was supposed to speak English. Indian kids were punished if they were caught speaking their tribal language.

As the wife of a middle class American male she was not allowed to work outside of the home and became an alcoholic.

According to my mother my grandfather was incensed by my mother going to university and threw her steamer trunk down stairs.. He was incensed by Volpert who lived near and in addition to being a male chauvinist was possibly disturbed by my mother’s intelligence in comparison with that of his daughters. Unfortunately I could not believe much of what my mother said. She even bragged about her lying. “I could lie faster than a horse could trot.” When she died after seven years in a vegetative state I dealt with my feelings by writing “M is for the many things she told me” which was published in Australian Short Stories and found elsewhere on this site.

Now I look back and feel bad that I wasn’t more understanding of her sense of frustration.

I had even erased her alcoholism from my mind. Years later William, my older son, recalled visiting my parents as a small child. He told me of an argument my parents had when my father hid her stash of booze.

With age sometimes comes understanding. My first wife, Elizabeth, used to quote a Pennsylvania Dutch saying, “We grow too soon, old, and too late smart.

“The apple falls not too far from the tree.” is a saying my mother was fond of iterating. It is possibly the truest thing she ever said. As I grow older I find myself repeating patterns of behaviour of my parents.

Reiterate is a word people often use. However, ‘iterate’ means to repeat so reiterate is an unnecessary word. My fondness for the word, iterate, is a hangover from my work in the computer industry.

One could never be at ease with mother because an argument could appear as rain from an apparently cloudless sky. Past wrongs would be brought up.

Father: How do you feel this morning, Martha?

Mother: You don’t care how I feel.

When I heard that I headed for cover so I wouldn’t be around for the subsequent doings.

One defence I had was to get her laughing. I was a little kid with a big vocabulary. She got angry at me and was in full flight. I remember saying, “You would wreak your vengeance on a defenceless child?” She stopped, looked at me and laughed. On to the next confrontation.

“I am sorry” and “I was wrong.” were expressions that I don’t remember my mother using. If caught in a lie she would go into defensive mode. Once I remember my father called the doctor because mother was in pain. As the doctor left he told me that my mother had a digestive upset. I went to mother’s bed, and she told me that she was feeling better and had recovered from her ‘heart attack’. I told her that the doctor said she had indigestion. “What does he know?”

Mother (She was never mum, mom or mummy, always mother) appreciated that I occasionally wanted to be left alone. In back of the house at 1605 East Genesee St. was a tall tree. I would climb the tree with a rope and book. I could lower the rope, and mother would tie a meal on it. The tree was a refuge.

Books were also my refuge. I liked to read, and father called me ‘a reading fool’. Mother, on the other hand, kept me supplied with books.

In kindergarten we were given lessons in reading readiness. I remember Mr. Carrot represented the letter “I”. As I could already read I was bored and became a nuisance so I was expelled from kindergarten.

Mother thought I might have a high IQ so she arranged an IQ test for me. The test confirmed it so she took me to the principle of Madison School, Mr Dunham, to try to get special classes for me. Mr Dunham took a look at snot-nosed, tow-headed me and sagely said, “They must have made a mistake.”

Mother was vain about her appearance. Her red hair and green eyes were striking. Once she gave me a picture of herself labelled “Your glamour girl mother.” I was disgusted as that was not the kind of mother I wanted.

When I got to adolescence I started having wet dreams. It was a big worry as I thought there was something wrong with me. I would get at night after one of those episodes, go to the bathroom and get cleaned up. Later mother told me she knew of those episodes. It would have given me peace of mind if I had told it was a natural happening.

When I was 12 or 13 I was in bed for several months with what was thought to be rheumatic fever. Mother thought of me as an invalid from then on. Since I am 97 with no history of heart trouble after that I don’t think I ever had rheumatic fever or a rheumatic heart. At 17 I wanted to join the army and do my bit in WW2. I needed parent’s consent because of my age. My mother supplied her consent since she was sure they would never take me.

At the recruiting station recruits were required to take an oath to defend and protect the Constitution of the US. I thought about it and hung back. I knew that the learned justices of the US Supreme Court often disagreed on what was constitutional. I thought it unreasonable that the army expected a 17 year old boy to know when an order was constitutional. The recruiting sergeant barked, “Are you in or out?” With misgivings I stepped forward and took the oath. When I got home and told mother I was in the army she was shocked.

In university I was very attracted to Julie. She reciprocated the attraction and invited me to come to Long Island and meet her parents. Then Julie no longer wished to see me. I was devastated. What had I done? I was heart-broken. For a long time I grieved at the abrupt and inexplicable ending.

Years later I visited my parents with my wife, Elizabeth, along with our two children, William and Seth. Rebecca was not born yet. Mother said, “You see those two beautiful children. You should be grateful to me for them.” “What do you mean, mother?” “Remember Julie who you liked so much? I had a talk with her and convinced her that she was not for you.” I found it difficult to be appreciative.

Footnotes

In writing I have consulted or quoted from the following references.

Dunlop, D. M., The History of the Jewish Khazars, NY: Schocken Books, 1967

Eliach, Yaffa, There Once Was a World, Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 1998

Gilbert, Martin, Jewish History Atlas, NY: Collier (Macmillan), 1976

Gilman, Sander L. and Jack Zipes, ed., The Companion to Jewish Writing and Thought in German Culture, 1096-1996.

Gould, Stephen J. ed., The Book of Life, NY: W. W. Norton and Company, 2001

Margulis, Lynn and Karlene Schwartz, Five Kingdoms, NY: W. H. Freeman and Company, 1998

Samuel, Maurice, In Praise of Yiddish, Chicago: Cowles Book Company, 1971

Shepherd, William R., Historical Atlas, NY: Barnes & Noble, 1966

Werblosky, R. J. Zwi and Geoffrey Wigoder editors, The Encyclopedia of the Jewish Religion, NY: Holt, Reinhart and Winston, 1965

[1] ibid., p. 121

[1] ibid., p. 190

[2] Reb is a term of respect in Yiddish roughly equivalent to mister.

[3] Eliach, op. cit., p. 53

[4] Werblosky, R. J. Zwi and Geoffrey Wigoder editors, The Encyclopedia of the Jewish Religion, NY: (Holt, Reinhart and Winston, 1965) p. 239

[5] Yiddish for little girl

[6] Eliach, op. cit., p. 388

[7] ibid., pp. 388-390

Life and death

When I was five years old I saw a little boy get killed. It was the same day we moved into a new apartment at 1605 E. Genesee St. in Syracuse, NY. The boy ran out into Genesee St. to retrieve a ball, bent over and the left front tire of a car ran up his back. Later that night I started to cry thinking of the boy. I told my father I was afraid to die. He held me and told me that we all eventually die. It is unlikely to happen until we get very old. By then we might even welcome it. I felt better but didn’t put it entirely out of my mind. I don’t remember ever consulting my mother when the world seemed wrong or threatening.

My grandmother’s legs

I would spend summers and sometimes more with my Grandmother and grandfather in Lake Placid, N. Y. up in the Adirondacks. I became very afraid of losing my grandmother. I didn’t want her or my grandfather to die. I can remember the odour of liniment that she used on her aching body. I recall her scent of clean clothes, garden and liniment. I keep her bottle of Sloan’s liniment.

Her legs were shapeless sausages with the oedema that afflicts some old people when they retain fluids. Sloan’s helped to ease her aching body.

I asked, “Ma, why are your legs so thick?” I called her ‘Ma.’ Her children did so why shouldn’t I?

She looked at me and held me close. In a dreamy voice she said, “When I was a young and beautiful woman in Eishyshok on a starry night I went swimming in the river. The smell of cedar and the reflections in the water so took me that I was not aware of the nearby water mill until I was drawn into the water wheel. I was so battered that my legs were no longer shapely when I got out. That’s why my legs are like this.”

Of course, I believed my grandmother. She was rigidly honest and would not lie to me. It was only years later that I realised that she did not want me to think of the infirmities of age. However, I did think of age. I heard that eating eggs promoted longevity so I advised my grandmother to eat eggs. Somehow, I knew this good time would not last.

However, her story wasn’t entirely fiction. There was a town of Eishyshok in Lithuania, and there was a mill. Eishyshok was founded in 1065 and its Jews (80% of the population) were murdered in 1941. Gravestones date from 1097 in the old Jewish cemetery. I have been able to find out about Eishyshok from Yaffa Eliach’s book There Once was a World. The picture of the mill with water wheel is from her book. To me Eishyshok is a town of ghosts. I will never go there.

My grandmother and grandfather

Literature may reflect life. As a teenager I often disliked my parents and felt very guilty about disliking my parents. Then I read a book which liberated me from my guilt. The protagonist, Ernest Pontifex, lived in the nineteenth century, had far worse parents than mine and hated them far more than I hated mine. He was depicted as a very decent man who broke off contact with his stifling parents. The book was The Way of All Flesh by Samuel Butler.

I read the book again several years ago and, to my surprise, still enjoyed it. One excerpt from the book:

To me it seems that youth is like spring, an overpraised season--delightful if it happen to be a favoured one, but in practice very rarely favoured and more remarkable, as a general rule, for biting east winds than genial breezes. Autumn is the mellower season, and what we lose in flowers we more than gain in fruits. Fontenelle at the age of ninety, being asked what was the happiest time of his life, said he did not know that he had ever been much happier than he then was, but that perhaps his best years had been those when he was between fifty-five and seventy-five, and Dr Johnson placed the pleasures of old age far higher than those of youth. True, in old age we live under the shadow of Death, which, like a sword of Damocles, may descend at any moment, but we have so long found life to be an affair of being rather frightened than hurt that we have become like the people who live under Vesuvius, and chance it without much misgiving.

The book is in a genre of fiction called bildungsroman.

Dying

I don’t remember it, but my father told me that I fought sleep when I was a little boy. I would say, “Eyes don’t close. Eyes don’t close.” Eventually they would close, and I would be asleep. I suppose I wanted to see what comes next and was reluctant to lose consciousness.

Death is not seeing what comes next. I still want to see what comes next.

Growing up

ItI think that reading books of that genre can be of great help to those who wonder where they are in life.

Assume by some standard you are grown up whatever that means. What is your purpose in life? Oops. Sorry I asked that since that is a bad question. One kind of bad question is that which assumes an answer. That question is bad since it assumes life has a purpose and we have but to find it. Some religions assume our purpose in life is to worship God and prepare for the afterlife. Since there is no reliable evidence of the existence of either it is reasonable to reject that as a purpose. I think it is useless to look for purpose. What am I doing here?

Why am I writing to you? What gives me the right? Who am I that I should write and you should read? Just as when I read “The Way of All Flesh” and felt there was something in me that was at one with all teenagers, there is something in me that is at one with all human beings that feel unique in themselves. Hobbes expressed it in The Leviathan”.

For such is the nature of men, that howsoever they may acknowledge others to be more witty, or more eloquent, or more learned; yet they will hardly believe there are so many as wise as themselves; for they see their own wit at hand, and other men’s at a distance.

You are the only expert on what goes on in your head. Be secure in that.

When multicelled humans grow up or even before that they usually have ideas of acts that are associated with reproduction. Human reproduction drives our culture. Most art and literature refer to that process so we may here consider human biology.

Humans appear in two forms – multicelled and single celled. The multicelled form has a mortality of 100%. The single celled form has a very high mortality rate, but a very few of the single celled forms unite with other single celled forms to produce the multicelled form. The single celled forms are sperm and ovum. The multicelled forms are male and female.

No species can increase indefinitely without an eventual catastrophe. If multicelled humans do not control their rate of reproduction in a rational manner the population will be controlled by pestilence, war and famine. Any suggestions? all begins with an idea. Maybe you want to launch a business. Maybe you want to turn a hobby into something more. Or maybe you have a creative project to share with the world. Whatever it is, the way you tell your story online can make all the difference.

Reflections

I have been asked to give what insights I have on the following subjects:

how to have a happy marriage

how to stay mentally active in your later years

how to find purpose in life after you finish work

how you stay so passionate about the world around you

It would be presumptuous of me to prescribe what other people should do to attain these ends. I can only tell what has happened to me and be aware that all of you who have been listening are different from me. All of you who have not been listening are also different from me.

I have a very happy marriage, and it is most joyous. I was attending a conference at Cambridge in 1980 when I walked into the office of Trinity College and was seized by instant lust. The dear object of my attention was living in Norway and I was living in Connecticut. We spent a wonderful time together until we returned to our homes in Norway and the US. We bid a tearful goodbye at Victoria Station, and we thought we would never see each other again. A couple weeks later I was back in Europe. Philips, the Dutch corporation I worked for sent me to the home office in the Netherlands. I asked them if I could go by way of Norway. That was ok with them as long as I showed up on Monday. We climbed a mountain near her home and looked down on beautiful Lake Øyern. Our evening meal that night included fungi and berries Marie gathered on the mountain. As I went back and forth from the US to the Netherlands I went by way of Norway. Marie came to the Netherlands, and we visited other countries. Eventually Marie came to the US, and we got married. She didn’t particularly like the US and wanted to go back to Australia where she was born, grew up and went to university. Since she came to the US for me I came to Australia for her.

That’s how my mother’s mother and my mother’s father came to the US. He was walking through her town and saw her. They were both supposed to marry other people, but so what. He came to the US after a time in England and sent for her. They decided the lower East Side of New York City was not a good place to raise children. So they took to the woods of the Adirondacks. They were nineteenth century hippies and nature lovers.

My father came to the United States in a different way. He was conscripted into the Russian army before WW1.

I was married before and have three great children. Their mother is now dead, but it was not a happy marriage. If there is any blame it is on me. Elizabeth was a wonderful woman, and I can think back and appreciate how wonderful she was. I am sorry I didn’t appreciate her when we were together.

If you have a happy marriage it might be plain dumb luck. Marie disagrees. She said she has worked darn hard at it. If you are in a bad situation but it is not too bad just make the best of it. If you want to change the situation think how it will affect others. I can give advice, but it would have been better if I had thought of it earlier. I hope all of you are wiser than I am.

How does one stay mentally active in later years? If one waits for one’s later years to become mentally active it is too late. If one develops interests outside of one’s work one can continue those interests after retirement. I have had varied interests and activities since I retired. They are:

Doing courses in philosophy and history at the University of Queensland.

Reporting and commenting on news at 4ZZZ.

Acting as adviser to Senator Woodley.

Editing Social Alternatives.

Travelling.

Seeing family.

Writing (published story and write essays for online opinion and other places)

http://onlineopinion.com.au/author.asp?id=4977 points to the articles for online opinion

Reading (mostly science, philosophy and nineteenth century fiction)

Mathematics (mainly number theory)

Playing games on the computer (too much)

Guiding people on nature walks at Osprey House and Roma Street Gardens (had to quit because of loss of high frequency hearing so could not easily hear voices of children)

The Queensland Mycological Society (They no longer wish me to go with them on foraging expeditions for fear I might have an accident)

Politics (am member of Greens, various nature organisations and liberal (in the US sense) groups)

Some of the above interests I had before I retired and some have developed since.

I have already spoken of purpose and indicated that it is not something I worry about.

How do I stay passionate about the world around me?

I think of George Washington who said, “"Let us raise a standard to which the wise and honest can repair.” At 89 I can’t even raise much of an erection. However, I find that I am not bothered by thinking about sex every minute and a half. I can focus better on what I am doing and can be more aware of the world around me. I have kept and nurtured my sense of wonder. One thing that helps that sense is the realisation that there is no God of the Gaps. We can always learn more about our world. There are many writers whose work is devoted to explaining the natural sciences, the physical sciences and mathematics. Seneca said, “Religion is regarded by the common people as true, by the wise as false, and by the rulers as useful.” Whether one is wise is possibly best for others to say. However, one can be wise enough not to accept the answers of the credulous.

Much of our medical resources are devoted to the last few months of life. I think it would be good if a person diagnosed with a terminal disease involving great suffering were given the alternative of assisted suicide which could be made available from that time forth. I think prevention of suicide where it is the most reasonable alternative is a social problem.

When I heard of Robin Williams’ suicide I thought of E. A. Robinson’s poem.

Richard Cory

Whenever Richard Cory went down town,

We people on the pavement looked at him:

He was a gentleman from sole to crown,

Clean favored, and imperially slim.

And he was always quietly arrayed,

And he was always human when he talked;

But still he fluttered pulses when he said,

"Good-morning," and he glittered when he walked.

And he was rich, — yes, richer than a king, —

And admirably schooled in every grace:

In fine, we thought that he was everything

To make us wish that we were in his place.

So on we worked, and waited for the light,

And went without the meat, and cursed the bread;

And Richard Cory, one calm summer night,

Went home and put a bullet through his head.

Possibly both Richard Cory and Robin Williams had very good reasons to end their existence. We cannot know. There is a cliché “A person died before his or her time.” Like many clichés it is nonsense. When we die is our time. We cannot determine when we are born, but we may determine when we die. That seems to me a human right.

After I attended a recent funeral I began to feel as though I have been ushering people off this mortal coil. On October 31, 2015 I will be 90, and death is much closer to me. In human mythology death is often personified so I’ll slip into the character of death for a moment: